Présentation

Des corps s’agitent et se font entendre. Ça chuchote, ça se renverse cul par dessus tête, ça miaule, ça court à l’intérieur et à l’extérieur des lignes verticales de béton, actualisant la rencontre entre les sujets perturbateurs hérités de l’avant-garde européenne Dada, et une architecture brutaliste, mettant à nu sa structure et sa matière, faite d’utopie.

Sous le titre Paper Tiger Whisky Soap Theatre (Dada Nice) l’exposition se concentre sur les relations entre jazz-scat (style vocal, propre au jazz, né au tournant du 20e siècle aux Etats-Unis qui privilégie la valeur rythmique et phonétique des syllabes à la signification des mots) et l’héritage du mouvement d’avant-garde Dada dont la première manifestation pluridisciplinaire et anti-art se déroula il y a tout juste 100 ans (le 7 février 1916) à Zurich avec le Cabaret Voltaire ouvert par Hugo Ball.

Ce dialogue fait suite au travail engagé par Sonia Boyce avec des performers vocalistes dans Exquisite Cacophony, vidéo présentée à la Biennale de Venise 2015.

Pour Sonia Boyce le jazz scat et Dada partagent une fonction identique au sein de l’avant-garde, celle de faire face à un « traumatisme social de grande envergure » (cf. entretien filmé avec Sonia Boyce) : la montée du fascisme, les conflits européens, puis la crise économique qui encadrent le paysage de l’entre-deux-guerres. L’un comme l’autre font jaillir des gestes spontanés, impromptus. Le tumulte, la frénésie et le tapage des corps s’insurgent contre la guerre et dénoncent alors la recherche d’un formalisme académique. A partir de cet héritage de défiance vis-à-vis du discours hégémonique, l’artiste met en place les conditions de jaillissement d’un langage commun partagé. Ce système de signes contestataires, révélé par la pratique de l’improvisation, agit comme un signal inscrit dans le non-sens.

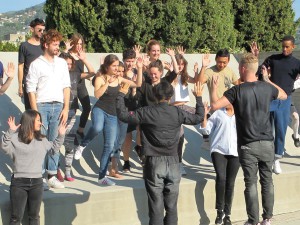

Affiliée aux pratiques collaboratives, Sonia Boyce a réuni lors de sa résidence à l’automne 2015 Vânia Gala (chorégraphe), Astronautalis (chanteur hip hop) et des étudiants de l’école d’art, pour un atelier d’improvisation au sein de l’architecture de la Villa Arson. Filmée par une équipe de tournage, dirigée par Michelle Tofi, les différents matériaux visuels et sonores issus de cette performance participative font l’objet de l’installation présentée dans la galerie carrée composée de vidéos, de dessins et d’un papier peint. Les vidéos composites et autonomes participent à l’éclatement de tout récit au profit de situations. Leurs durées n’excèdent jamais celle de la vidéo projetée The Circle (18 min.) Initiée par la répétition des termes Paper Tiger Whisky Soap Theatre, elle donne une impulsion sonore et rythmique à l’ensemble.

L’une des caractéristiques de l’approche de Sonia Boyce est un cadrage inclusif qui donne à voir l’équipe de tournage.

Ainsi, son travail s’écarte d’une documentation de performance au profit d’une monstration à la fois des enjeux actuels de captures du réel par l’image, tout autant que des manières de voir, qu’induisent les modalités d’accrochage et de diffusion des images (John Berger, Ways of Seing, 1972). Ce cadrage implique également d’autres regardeurs ou locuteurs à l’intérieur de l’image, notamment le spectateur et le badaud. Si le premier est volontaire, le second peut se trouver dans un inconfort. Ainsi, le visiteur de l’installation est pris dans un jeu de situations d’énonciations distinctes, avec lequel il doit composer entre rire et malaise.

Aussi le cœur du travail de Sonia Boyce n’est-il pas d’interroger la production et la réception de gestes non attendus ? Et notamment quand il vise la nature du rire, lieu d’inquiétude, d’effroi et de joie émanant d’un écart ou d’une prise de distance entre le sujet et une norme acceptée comme évidence.

Sophie Orlando

Commissaire de l’exposition, historienne de l’art, chercheure et professeure à la Villa Arson, elle effectue depuis 2006 des recherches sur le British Black Art.

Interview

Biographies

Sonia Boyce (née en 1962) s’est faite connaître au début des années 80 en tant que figure clé de la scène artistique British Black Art, devenant une des artistes les plus jeunes de sa génération à entrer dans les collections de la Tate Gallery. Sa production artistique était alors associée à un retour de la peinture figurative, sous les traits de l’identité raciale et genrée dans le contexte britannique thatchérien (Lay Back Keep Quiet and Think of What Made Britain So Great, 1986).

Or ses œuvres photographiques, Tongues (1997) ; ses papiers peints, Clapping Hands (1994), Lovers’ Rock (1998) ; ses installations, Afro Blanket (1994) et ses vidéos, The Audition (1998), montrent dès les années 1990 un intérêt accru pour la chanson, la musique et le son, à travers une dimension archivistique, performative et le développement d’une pratique collaborative.

Cette articulation s’exerce désormais au sein d’installations et de vidéos, manifestes d’improvisations, lesquelles évoquent les relations de pouvoirs interpersonnels ainsi que les négociations entre l’histoire officielle et la mémoire collective (Dance of Belem, 2011; Move, 2013). Performeurs, chanteurs, vocalistes, danseurs et badauds redéfinissant les enjeux actuels des pratiques collaboratives sous le cadrage des caméras.

Nombres de ses travaux sont présents dans les collections nationales britanniques (Tate Modern, Arts Council Collection, British Council, Victoria and Albert Museum, Government Art Collection, Whitworth Art Gallery).

Inclus dans ses expositions personnelles : Devotional, National Portrait Gallery, Londres (2007) ; Crop Over, Harewood House, Leeds et Museum & Historical Society de la Barbade (2007/2008) ; For you, only you (Paul Bonaventura), Ruskin School of Drawing & Fine Art, Oxford University et tournée (2007/2008) ; Like Love, Spike Island, Bristol et tournée (Green Box Press, Berlin 2010) ; Scat : Sound and Collaboration, Rivington Place, Institute of International Visual Art (2013).

Elle participe régulièrement à des biennales internationales comme Praxis : Art in Times of Uncertainty, 2e Biennale de Thessalonique, Grèce (2009) ; The Impossible Community, Moscow Museum of Modern Art (2011) ; Play ! Recapturing the Radical Imagination, 7e Biennale internationale d’art contemporain de Göteborg (2013) ; All the World’s Futures, 56e Biennale de Venise (2015).

Professeur d’art depuis 1986, l’artiste a souligné le rôle prépondérant de l’école d’art comme lieu de recherche générateur de sa pratique. Sonia Boyce est également chercheure et directrice du projet « Black Artists and Modernism » financé par le Arts & Humanities Research Council (UAL/université de Middlesex, Londres).

Charles Andrew Bothwell (né en 1981), plus connu sous son nom de scène Astronautalis, est un artiste américain du hip-hop alternatif actuellement basé à Minneapolis, dans le Minnesota. Après avoir atteint une certaine notoriété locale à Jacksonville en Floride et avoir participé au concours Scribble Jam, Astronautalis a auto-produit son premier disque You and Yer Good Ideas (Toi et tes bonnes idées) en 2003. Il a ensuite signé un contrat avec Fighting Records et le disque a été ré-édité en 2005, suivi par un deuxième disque en 2006, The Mighty Ocean and Nine Dark Theaters (L’océan puissant et neuf théâtres obscurs). Son troisième disque Pomegranate (Grenade) a été produit par Eyeball Records en 2008. L’hiver 2009 il a fait une tournée européenne avec le groupe canadien indépendant de rock Tegan and Sara, qu’il a produit à nouveau au printemps 2010 en Australie. Son quatrième disque, This Is Our Science (C’est notre science), a été produit par Fake Four Inc. en 2011. Il descend de James Hepburn, le quatrième comte de Bothwell, une des raisons pour lesquelles ses paroles traitent souvent de fiction historique. Andy a collaboré avec Sonia Boyce à un précédent projet inspiré par l’art du spectacle intitulé Exquisite Cacophony, avec la chanteuse Elaine Mitchener (2015).

Michelle Tofi graduated from London Metropolitan University with a first class honours degree in Film and Broadcast Production in 2011. Since then she has specialised in cinematography and self-shooting, having content she shot for BBC Worldwide screened in 76 million homes across the globe, and travelling to shoot in France, Sweden, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Bahrain and Qatar. Her corporate clients have included Ray-Ban, the Gaurdian, YouTube and Adidas although her passion is for fiction and art filmmaking, and she has collaborated extensively with artist Sonia Boyce, MBE on three video projects. Michelle is also keenly interested in documentary work, and is currently producing her first feature length documentary, « Drag it Out in the Open ».

Richard Thomas is a Sound Recordist and Musician. He’ll record most sounds (within reason) and a number of them have been featured on TV, film and videos on the internet (some feature cats). He will sometimes make noises (sometimes under duress). He has been accused of making Art before. His favourite cake is Battenburg. He regularly refers to himself in the third person.

Vânia Gala (née en 1972) est chorégraphe et chercheuse. Elle est titulaire d’un BA en Danse du E.D.D.C. (European Dance Development Center) Hogeschool voor Kunst – Arnhem, (Pays-Bas) et d’un MAC avec mention du Conservatoire de musique et de danse de Trinity Laban. Depuis 2015 elle est doctorante à l’université de Kingston après avoir reçu une bourse FASS. Les chorégraphies de Gala, ses partitions et ses lectures–performances explorent le potentiel de l’absence (et du non-humain) dans l’art chorégraphique à travers des actes de dérobade, des procédés d’auscultation et une attention aux choses ou aux systèmes invisibles en tant que personnages principaux de la performance. Depuis sa première représentation, sa pièce – Automatic Id (AID) à été jouée en Angola, au Portugal, en Norvège, en Allemagne, en Irlande, en Grande-Bretagne et en Russie. En 2005 (AID) a reçu le prix “Best Female Performance” (meilleure performance féminine) au Dublin Fringe Festival, et a été montrée au Aerowaves Festival (Londres) et à la première triennale de Luanda (Angola). En 2007 Gala s’est produite au premier pavillon africain de la biennale de Venise. MiamiLuanda a été présenté pour la première fois au Teatro Académico Gil Vicente en 2009 et a ensuite été présenté lors de la plate-forme portugaise pour les arts de la scène 2009 commissariée par Rui Horta. 8º10’30 » a été joué au TAGV et au Centro Cultural de Belém (CCB) en 2010. Elle a récemment collaboré dans le domaine des arts visuels avec Sonia Boyce sous le commissariat de Paul Goodwin (Tate), une collaboration présentée à la CCB et au Georgia Scherman Projects, Toronto. En 2012 elle a créé “Invited Guests” (« hôtes invités »), qui a été joué au théâtre Bonnie Bird. Ses projets les plus récents incluent “Cooling Down Signs”, une commande européenne de Beyond Front@ qui a été jouée au festival de la semaine de la danse à Zagreb (Croatie), à D.I.D (AT), Front@ Festival (SI), Bakelit (HU), et “35 Days of Nothing to Say“ (« 35 jours avec rien à dire »), un projet de recherche continue joué à The Place and Dance 4 (Royaume-Uni). Elle a publié des écrits pour Emergency Index et pour le catalogue du pavillon de l’Angola lors de la 56e biennale de Venise 2015.

Programme associé

3 – 4 mars 2016 : rencontres & interventions autour de l’exposition

Ce programme pour tous les publics a pour objectif d’appréhender le travail de Sonia Boyce dans ses enjeux artistiques, contextuels et historiques, à travers les interventions de commissaires, historiens de l’art, critiques d’art, et performers.

Il propose une réflexion sur les gestes dansés et le mouvement au sein de Dada, une analyse des filiations entre les scènes jazz, les artistes fluxus et les artistes contemporains, et discute le point de vue des artistes sur l’écriture curatoriale actuelle de l’histoire coloniale.

Jeudi 3 mars :

14h, ouverture par Jean-Pierre Simon, directeur de la Villa Arson

14h15, introduction par Sophie Orlando, historienne de l’art et commissaire de l’exposition

14h45, Sonia Boyce, artiste : « In the process, someone became a cat and another became a seal »

15h30, Cécile Bargues, historienne de l’art : « Dada, la danse, le fantôme »

17h, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, commissaire d’expositions : « Looking at Akinbode Akinbiyi and Ben Patterson to Answer Curtis Mayfield’s Calls in We the People Who Are Darker Than Blue »

17h30, Lotte Arndt, critique : « Connexions transcontinentales et transhistoriques : Sammy Baloji »

19h, Film : Reece Auguiste, Twilight City, 52 min, 1989. Black Audio Film Collective.

Présentation du film par Sophie Orlando. en partenariat avec L’ECLAT

Vendredi 4 mars :

14h, 14h30 et 15h, Performance : Latifa Laâbissi performe « Samouraï » (5′) et « Phasme » (9′)

(3 fois dans l’après midi)

Programme détaillé des 3 et 4 mars à télécharger

Interventions en français et en anglais

Entrée libre

Bibliographie

Cette bibliographie succincte présente quelques clés de lecture de l’exposition Paper Tiger Whisky Soap Theatre.

Artificial Hells de Claire Bichop permet d’inscrire la pratique collaborative de l’artiste au sein d’une filiation artistique héritière de l’avant-garde dada, au situationnisme, au happening jusqu’au renouvellement des pratiques participatives autour de 1990 à partir d’un retour de l’espace social au sein du modernisme européen.

Gilane Tawadros, Mark Crimson, Sophie Orlando offrent des outils de compréhension du travail de Sonia Boyce, à la fois dans sa pratique de la peinture et du dessin des années 1980, tout comme dans sa pratique performative développée à partir des années 1990.

La lecture de l’ouvrage Ways of Seing de John Berger rappelle combien l’image artistique est médiée par son mode de présentation (curatorial, ou discursif) et invite

à analyser le rôle prépondérant du cadrage de l’image dans l’installation de Sonia Boyce par la grille du papier peint, la présentation physique sur moniteur ou sur écran projeté.

D’autres références accompagnent le croisement entre le Jazz Scat et Dada, convoqué par l’artiste, et situent l’apport des Cultural Studies et des Black Feminist Studies, dans sa lecture de l’espace de représentation.

David A. Bailey, Sonia Boyce, Ian Baucom (ed.), Shades of Black: Assembling Black Arts in 1980s Britain, 2005

John Berger, Ways of Seing, Penguin, 1972

John Berger, Voir le voir, B42, 2014

Claire Bichop, Artificial Hells, Participatory and the Politics of Spectatorship, Verso, 2012

Sonia Boyce, Like Love, The Green Box, 2010

Marc Dachy, Dada et les dadaïsmes, Folio, 2011

Judith Delfiner, Double-Barrelled Gun –Dada aux Etats-Unis (1945-1957), Les presses du réel, 2011

Stuart Hall et Jacques Martin, New Times, The Changing Face of Politics in the 1990s, Lawrence & Wishart, 1989

Heidi Safia Mirza (ed.), Black British Feminism, A Reader, Routledge, 1997

Nikos Papastergiadis, inIVAnnotations: Sonia Boyce – Performance No. 2, The Institute of International Visual Art (INIVA), 1998

Jed Rasula, Destruction was my Beatrice, Dada and the Unmaking of the Twenthieth Century, Basic Books, 2015

Gilane Tawadros, « Beyond the Boundary, The Work of Three Black Women Artists in Britain », dans Houston A. Backer, Mantha Diawara et Ruth H. Lindeborg (éds.), Black British Cultural Studies, A reader, University of Chicago Press, 1996, p. 240-277.

Gilane Tawadros, « Black women in Britain, A personal and Intellectual Journey », dans Third Text, n° 15, 1991, p. 71-76.

Gilane Tawadros, Sonia Boyce, Speaking in Tongues, Kala Press, 1997

Texte en ligne

Sophie Orlando, « Sonia Boyce : stratégies artistiques post-1989 », Critique d’art [En ligne], 43 | Automne 2014 – Lire le texte complet

Lien

http://www.theses.fr/2010PA010668 : Orlando Sophie, « What makes Britain So Great ? » La britannicité et l’art contemporain de 1979 à 2010 en Grande-Bretagne, sous la direction de Philippe Dagen, Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne, soutenue en 2010 à l’INHA.

Autour du Workshop

Participants

Équipe Sonia Boyce

Sonia Boyce

Directrice artistique / Artistic Director

Vânia Gala

Performer

Andy Bothwell (Astronautalis)

Performer

Alice Labant

Performer

Michelle Tofi

Directrice de la photographie / Director of Photography

Richard Thomas

Ingénieur du son / Sound Recordist

Basak Bayhan

Second assistant caméra / Second Camera Person

Joe Stone

Troisième assistant caméra / Third Camera Person

Jessica Taylor

Assistante de production / Production Assistant

Maya Bailey

Photographe / Stills Photographer

Étudiants Villa Arson

Sharon Alfassi

Claudio Arnell

Clarisse Charlot-Buon

Johan Christ-Bertrand

Felicia Cleveland-Stevens

Anne-Sophie Duforets

Coline Dupuis

Daisy Gray

Mariana Guedes

Marja Heiskanen

Dong Eeg Kim

Sori Kim

Louis Kiock

Néle Lavant

Paul Lemaire

Marvin M’Toumo

Salomé Martin

Clémence Mauger

Ariidehav Michaud

Lauriane Norgiolini

S Paret

Louise Ronk-Senges

Damien Vongués

Dan Wu

Réaction au projet

par Richard Thomas

2015 – 2016

I’m a sound recordist. It’s a job that a lot of people don’t even realise exists, but it’s my job to capture the sync sound for picture as it happens. Most people assume ‘doesn’t the mic on the camera do this?’, they assume that whatever the camera ‘sees’ can be heard- more often than not all the camera mic will pick up will be a distant perspective on the action with high background noise and any movement the camera operator makes will be very present. So, my job is to get microphones closer to the things we want recorded. But in an improvised performance, how do I know what we’re going to want to record?

In my line of work I usually find that planning is really important to getting results; the more I know about what is happening, the more likely I’ll have the tools and personnel to be able to cover and deal with a given situation. However another skill I often have to employ is improvisation: something will be changed at the last moment, someone will neglect to tell me something they didn’t think was relevant and that can make a huge difference to me. I’ll be constantly trying to second guess what’s going to be thrown at me by people whose main concern is what something looks like. I’m also no stranger to improvisation in a more general artistic context- I’ve performed free improvised music for a number of years including work with artists in other contexts, such as dance and visual art. However, in this case I’m improvising more as a technician (which I’m possibly less comfortable with).

My first thoughts when Sonia approached me about this project were if and how the performance would be contained- how many performers there would be? What sort of sound they could be making? What the space would be like? All these questions were open ended so I packed kit for as many situations as I could think of happening and assumed (wrongly) that as the process went on that I’d have more of an idea what was going to happen during the performance and looked into where I could get additional equipment if required locally and the process emerged.

Over the two days before the performance, we started looking around the grounds at Villa Arson and found so many interesting spaces. I really enjoyed the brutalist aesthetic of the architecture, and also how its structure allowed green spaces and plants to grow in sections. I ended up taking far too many photos of the place… I also considered what impact each space would have on me being able to capture the performance, either looking at the amount of space available (the more restricted, the closer I could get microphones on stands and be able to cover the area adequately) and how much background noise there would be.

The day before we also filmed both Andy and Vania working with the students. To be honest, the things both of them were doing with the students were pretty much the scariest things I could imagine dealing with for something like this on a technical level: Andy’s group were doing very low level dialogue – sometimes whispered to each other (and some of his group weren’t the most extrovert of people either), while Vania’s were climbing on top of each other. The reasons for this are that low level dialogue requires close microphones to pick it up, even if you were standing a few metres away you’d struggle to hear what the person is saying, and this is with your brain concentrating on them (see the ‘cocktail party’ or Haas effect) and microphones can’t distinguish individual voices like your brain can. Personal microphones would need to be mounted on the body of the performer and could easily get moved/unstuck and pick up clothing noise easily, so adding movement with climbing on top of each other would limit what they would pick up.

So, when the performance (or “happening”?) began I decided to use as many personal microphones as possible on a variety of performers, mainly so we got a mixture of languages close up and one who said they had an idea based around a song. I also had a stereo microphone setup on a boom to capture a wider perspective. However, I still needed to have a portable rig and it was too late in the day to order in more equipment (let alone enough to have a microphone on everyone…). I had to make sure the microphones and radio transmitters were securely attached to the performers and wouldn’t move, even when doing some physical things. Even after it had started I thought we may stop before moving location, however it didn’t- I was stuck with this setup and had to improvise, running after the performers!

Afterwards, I thought that both through the aesthetic of the buildings and the nature of what the performers were doing that it did have a very 1960s experimentalist feel to it, where I imagine the students of, say Black Mountain College with John Cage and Merce Cunningham may have done similar things- they’re reconsidering what can be considered art, music or performance and not letting things like training determine whether you’re “allowed” to perform like this or not. It’s the sort of environment which encouraged experimentation and allowed performance art to come into its own.

When I’ve worked with Sonia before I know she doesn’t really mind seeing crew and equipment, also I think part of drew me to my job is my ability of avoiding photographs. I do like the fact that the ‘workings’ are revealed (and I’m also doing that here a little).

I’d still avoid being in frame as much as possible, although it’s hard to avoid 3 cameras, there are also a few wireless packs showing, which isn’t too surprising, given some of the movements the performers were doing and their clothes will move. In this case I don’t mind, although feel a little self conscious, but on a different job I would!

Much later, when editing and mixing the audio afterwards I was generally pleased with what I got when cleaned up and re-cut together from all the individual microphones (it was too manic and unpredictable to get a good mix on location): I expect we were lucky, although there were some parts which had issues (Vania was very prominent in the library section and didn’t have a personal mic, I had to use sound from the boom and camera mics to cover this as I couldn’t be next to her all the time) and we didn’t always have the options of a close perspective in some of the whispered sections when performers were not near a microphone.

Everything you hear in the installation was recorded during the performance, ‘live’. There’s an incredibly (biologically) intimate moment which came out of something which would normally be considered ‘wrong’: One of the performers’ microphones gets pushed hard against their chest in the ‘amphitheatre’ section both muffling their voice but also picking up their heartbeat- I edited it in order to make this effect more prominent. It’s the only thing in the piece that pushes the viewer into a more abstract, internalised perspective, although some of the whispered moments are very personal and although captured in a documentary style, doesn’t necessarily fit with that perspective.

The final installation involved playing all the videos back in the same room at once and there’s a wide dynamic range across them, with levels varying between whispers and shouts. We wanted to try and keep the intimacy of the quieter sections in the ‘circle’ and ‘amphitheatre’ videos so that they could be heard, while allowing the full chaos of the ‘library’ and ‘battle’ sections to be brought out. We came up with a sequence so that each of the videos runs for approximately the same time, however I expect it’ll never be quite the same as they’re all running independently, but at least all the loud sections shouldn’t happen at the same time as the quieter ones

Informations pratiques

Horaires

Exposition ouverte tous les jours de 14h à 18h sauf le mardi

Du 30 janvier au 30 avril

Accès

Tramway : Ligne 1, direction Henri Sappia, arrêt Le Ray

Puis, 10 mn de marche, suivre signalisation via les rues Paul Mallarède et Joseph d’Arbaud.

Bus : n° 7 et 4, arrêt Deux avenues

Puis, suivre signalisation av. Stéphen Liégeard – Villa Arson.

Autoroute A8 : sortie N° 54, Nice Nord, direction Centre Ville, puis suivre signalisation Villa Arson

Depuis la Promenade des Anglais : suivre Bd Gambetta, puis Bd de Cessole, puis suivre signalisation Villa Arson

Contact

Service des publics

+33 (0)4 92 07 73 84

servicedespublics@villa-arson.org